All Tied Up?

Tying-Up or ER (exertional rhabdomyolysis) is a problem that every yard will encounter at some point in time with reports of 5-7% of the thoroughbred population being affected.

ER is the general term used to cover two main forms of tying-up, acute or recurrent. ER by definition relates to the breakdown of striated muscle fibres following exercise. These fibres connect to the bone allowing movement of the skeleton. Damage causes anything from mild stiffness to the inability to move.

With much still unknown about the condition the focus falls on reducing risk and ongoing management of those affected with recurrent form. There are 4 key factors to consider when looking to minimise risk, and to consider when reviewing why an episode of tying-up has occurred.

Acute Exertional Rhabdomyolysis

The acute form is typically caused through factors external to the muscle rather than their being an intrinsic muscle defect. The acute form is infrequent and sporadic in nature.

Exercise

The most common cause is adaptation to a new workload or style of work, for example increasing work on a deeper surface or an increase speed work. The soreness may be immediately noticeable post work or on the following day. Such episodes are a case of delayed onset of muscle soreness, much like the soreness we experience after an intense workout or upping the length of a run.

Where speed work is concerned the most likely cause is a depletion of cellular high energy phosphates, the muscles energy supply, combined with lactic acidosis. Where endurance work is concerned depletion of intracellular glycogen, the stored form of glucose, often combined with over-heating and electrolyte imbalances is the common cause.

Weather

The unpredictable and sudden changes in weather can play a part in an acute episode. A piece of work on a cold morning or race in the afternoon heat can cause problems with muscle function, be that cramping or fatiguing.

Stress and Excitable Behaviour

Both can cause a sudden case of tying-up and are sometimes hard to manage. Some horses are certainly more susceptible than others. A simple change to a routine, for example going out last lot rather than in the usual first lot, can be enough of an upset to cause an episode. Sometimes the cause is more identifiable, with a rider reporting over excitable behaviour under saddle.

Excess Energy Intake

The other key factor for an acute episode is dietary energy intake being excessive to the current level of work. The use of high starch feeds to supply energy for horses in training is a common practice. Starch is a needed nutrient and should not be thought of a something to eliminate from a diet, however, its intake needs to be carefully balanced against the workload. In the early stages of training, an imbalance of intake versus requirement can more easily occur.

Recurrent Exertional Rhabdomyolysis

This form of ER where episodes are frequent and often seen even at low levels of exercise had led to the suggestion that much like humans, there is an inherited intrinsic muscle defect. Such defects would predispose the horse to ER. Documented defects relevant to thoroughbreds include a disorder in muscle contractility or excitation contraction coupling, whereby muscle fibres become over sensitive and normal function is disrupted.

The risk factors to manage are the same for both acute and recurrent forms. The main focus often falls on dietary practices as this element is the easiest to control. Where possible pasture access on a daily basis is also recommended alongside changes to the feed bucket.

Dietary Considerations for ER

For those with the recurrent form the diet must be orientated towards less reliance on starch than traditional grain-based feeds, alongside use of other energy sources to meet daily requirements.

Quantifying ‘Low starch and high fat’ feeding

The recommended practice for management of ER is a reduction in starch and an increase in fats. This practice has two ways of benefiting the horse, a reduction in ‘spookiness’ or reactivity and a positive effect on muscle damage as seen by lower CK (creatine kinase) levels following exercise.

Positive effects on lowering CK levels have been found during research into feeding racehorses when a higher proportion the energy fed came from diets higher in fats, and lower in non-structural carbohydrates (starches and sugars), than traditional sweet feeds. The effect was noted when fed at 4.5kg/day, an amount easily reached and normally surpassed when feeding horses in training. The beneficial diet provided 20% of energy from fats and only 9% from starches and sugars compared to the more traditional sweet feed diet providing 45% of energy from starches and sugars and less than 5% from fats.

Finding Fats

Top dressing of oils is will increase fat in the diet with a normal intake of up to 100mls per day. Although the horse can digest higher amounts, palatability usually restricts a higher intake. Pelleted or extruded fat sources are increasingly popular as alternatives to oils for their convenience of feeding and palatability. Straight rice bran and blends of materials such as rice bran, linseed and soya are available from most major feed companies. Oil content will typically range from 18-26% providing 180g-260g of oil per kilogram as fed.

Racing feeds will also provide oil in the diet, content is quite varied typically from 4-10% providing 40g-100g per kilogram as fed. Hay and haylage also contains oil at a low level, typically 2%, providing just 20g per kilogram on a dry matter basis.

CHOOSING CARBOHYDRATES

Traditional feeding based on oats and other whole grains will have a higher starch content than feeds using a combination of grains and fibres. Levels of starch found in complete feeds and straights has a broad range from as low as 8% in a complete feed specifically formulated to have a low starch content, up to in excess of 50% for straights such as barley and naked oats.

Starch content of commonly fed straights and forage

| Material | Typical starch content % | Starch content per kilogram (2.2lbs) as fed |

|---|---|---|

| Hay | 1.8% | 18g |

| Oats | 37% | 370g |

| Naked Oats | 52% | 520g |

| Barley | 53% | 530g |

| Maize | 63% | 630g |

| Rice bran | 22% | 220g |

| Sugar beet (dry weight) | 1% | 10g |

| Alfalfa | 2% | 20g |

The level of tolerance a horse has for starch intake when suffering from recurrent ER is somewhat individual, but the general practice is to reduce the intake of starch as low as possible without compromising body condition, or providing an insufficient amount of energy to maintain performance. Starch is a valuable carbohydrate needed to provide glucose, the primary muscle ‘fuel’ required during anaerobic exercise where the horses’ heart rate is elevated and the pathway for utilisation of fats is closed. For horses in training a large part of the exercise program is anaerobic and therefore starch is required in the diet.

There is no official value at which a feed goes from being a high starch feed to a low starch feed. That combined with a lack of information around starch levels for some products can often result in yards having feed programs that are accidentally higher in starch than intended for their horses with ER. A common error is use of a pony feed or cool feed which is assumed to be more suitable by description but may not be low in starch, only lower in protein than a racing feed.

Feed materials today are wide ranging, allowing companies to create a variety of feeds around different nutritional parameters. It is possible to have a 14% protein feed with a starch content ranging anywhere from around 10% up to 35%. Protein content is completely independent of starch content and cannot be used as a predictor as to what starch level of starch your feed may provide. Obtaining that information from your feed provider is essential when making an informed decision about your feeding program for horses with ER.

As the hard feed, whether straights or a complete feed, forms the largest part of the diet by weight for a racehorse, it is the most influential item when looking to regulate starch intake. When considering starch intake, the total intake needs to be calculated. The amount of starch in a feed is important, for example choosing a feed that is 10% starch is likely a good decision over a feed at 30% starch, but these are just numbers. How much is eaten of that feed in a day is important. Blending hard feeds with alternative energy sources such as beet-pulp, oils and alfalfa in the feeding program dramatically lowers total starch intake. Through using a ‘low starch’ feed in combination with alternative fibre and oil energy sources it is possible to create a very low total intake without compromising on energy.

Examples of the different feeding programs on total starch intake

Example one - 'High Starch' feeding

| Feed | Bowls | Weight (kg) | Starch Intake (g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morning Feed | 30% Starch Racing Feed | 1 | 1.5 | 450 |

| Lunch Feed | 30% Starch Racing Feed | 1.5 | 2.25 | 675 |

| Evening Feed | 30% Starch Racing Feed | 2 | 3 | 900 |

| Large handful Alfalfa | 0.5 | 10 | ||

| Total | 6.75 | 2025 |

Example two - 'Moderate Starch' feeding

| Feed | Bowls | Weight (kg) | Starch Intake (g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morning Feed | 18% Starch Racing Feed | 1 | 1.5 | 270 |

| Lunch Feed | 18% Starch Racing Feed | 1.5 | 2.25 | 405 |

| Evening Feed | 18% Starch Racing Feed | 2 | 3 | 540 |

| Large handful Alfalfa | 0.5 | 10 | ||

| Total | 6.75 | 1215 |

Example three - 'Low starch' feeding

| Feed | Bowls | Weight (kg) | Starch Intake (g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morning Feed | 10% Starch Racing Feed | 1 | 1.5 | 270 |

| Lunch Feed | 10% Starch Racing Feed | 1 | 1.5 | 270 |

| Small handful Alfalfa | 0.25 | 5 | ||

| Evening Feed | 10% Starch Racing Feed | 1.5 | 2.25 | 405 |

| Rice Bran | 0.5 | 110 | ||

| Beet Pulp (dry weight) | 0.2 | 2 | ||

| Large handful Alfalfa | 0.5 | 10 | ||

| Total | 6.7 | 950 |

Adjusting feed to workload

Regulating feed to match workload is another important factor in managing horses with recurrent ER. For days of rest or walking only the ‘hard feed’ should ideally be halved in weight. This practice starts with the evening meal given on the day before rest and continues until the end of the rest day. To meet appetite and maintain condition the fibre element of the diet needs to be increased to meet the gap left from feeding a reduced amount of hard feed. When soaked beet pulp and alfalfa or similar chaffs are included in the program these can easily be increased to in part replace the removed hard feed alongside an increased offering of hay or haylage. Oils can be fed as normal on a rest day.

Maintaining a balance

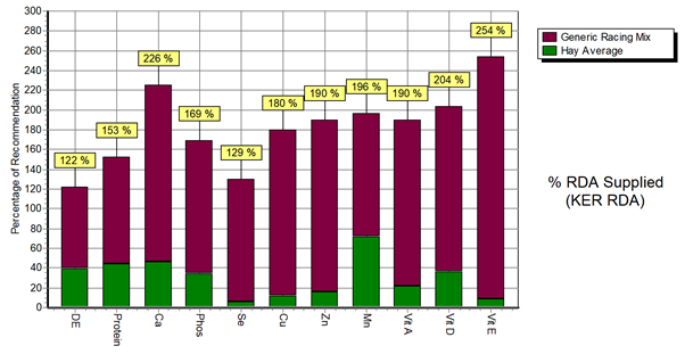

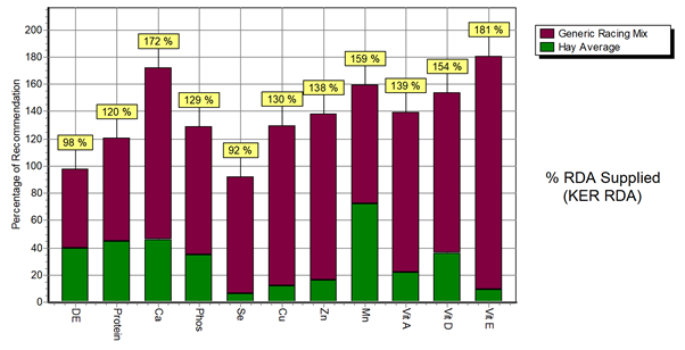

Where the individual horse determines that hard feed intake must be significantly restricted in order to avoid further episodes, it is worth considering if the diet is now providing appropriate levels of key nutrients. Feeds are formulated to be effective between certain ranges based on normal intake for that category of work. In general horses fed typical feeding rates will be provided with levels above baseline, eg greater than 100% for many nutrients, particularly those where benefits arise from a higher level of supplementation such as vitamin E.

The examples below show the impact of a reduced hard feed intake. Whilst intake is considered sufficient in meeting the majority of nutrient requirements, the recurrent ER horse with a lower feeding rate is no longer receiving the same level of nutrition, including receiving lower levels of vitamin E and selenium which could be of benefit. In such cases supplementing the diet through use of a vitamin and mineral balancer or specifically with individual nutrients concerned will ensure that the horse still receives a consistently high level of nutrition.

A total dietary intake assessment is provided by most major feed brands on request or through an independent registered nutritionist. Reviewing the diet as a whole will help identify where improvements can be made especially for horses with specific dietary needs.

Normal Intake

- 7.0kg (15 ½ lbs) of typical racing feed

- Free choice hay consumed at 1% of bodyweight

Reduced Intake

- 5.0kg (11lbs) of typical racing feed

- Free choice hay consumed at 1% of bodyweight

Kentucky Equine Research Recommended Daily Allowance

Other Dietary Considerations

Other nutrients often talked about when managing ER include vitamin E, selenium and electrolytes. Historically the inclusion of vitamin E and selenium were considered important for the prevention of further episodes, however there is no evidence to support such use. A case of deficiency in either of these nutrients may well put the horse at a disadvantage and could perhaps create a state where occurrence is more notable, however with the advent of fortified and balanced complete bagged feeds such nutrients are normally supplied in more than adequate amounts. Their role as antioxidants which function to ‘mop-up’ damaging free radicals generated through training is where their use can be of benefit to any horse at this level of work. The use of additional vitamin E is also recommended when increasing the fat content of the diet, a common practice when feeding horses with recurrent ER.

Electrolytes do play an important role in normal muscle function and any deficiency noted in the diet should be corrected. Identifying a need in the diet is more easily done than determining if the individual horse has a problem with absorption or utilisation of the electrolytes. A urinary fractional excretion test (FE) will highlight issues and subsequent correction through the diet to return the horse to within normal ranges may offer some improvement. However, it is important to note that for horses with recurrent ER, where an intrinsic muscle defect is present, the research to date has shown no electrolyte imbalances or differences between such horses and unaffected horses.

Summary

Feeding is an important part of reducing risk of an acute episode and in the management of recurrent ER horses. Understanding the starch intake of the total feed program and identifying any gaps or shortfalls in the diet will help you create a diet best suited to the individual. Including alternative energy sources in the feeding plan will create more flexibility in the program, particularly around rest days, and ensures appetite is met when hard feed must be reduced. If in doubt as to the contribution that a feed, forage or supplement is making to your feeding program consult your feed provider or nutritionist for further advice.

Feed Advice Form

Complete our online form to receive a detailed nutritional plan for your horse or pony from one of our registered nutritionists.

Quick Feed Finder

Use our quick and easy feed finder as a guide to select the right feed for your horse or pony.